No, Parliament Shouldn’t Get A Veto On Military Action

Why it was right for Rishi Sunak to act against the Houthi Militia without asking MPs

On Thursday night, Britain joined America in taking targeted military action against Houthi terrorists in Yemen. For months, the Iranian-backed militia have used Israel’s deployment in Gaza as an excuse to disrupt global shipping and access to the Suez Canal. In reality, they are an atrocious group acting as a proxy for Iran's desire to destabilize the Middle East and harm the West. Alternative trade routes involve navigating around Africa and shipping costs are up 300% as a result of their actions. The British government’s decision on Thursday is, in my view, strongly welcome. It is an act of defense against an evil empire.

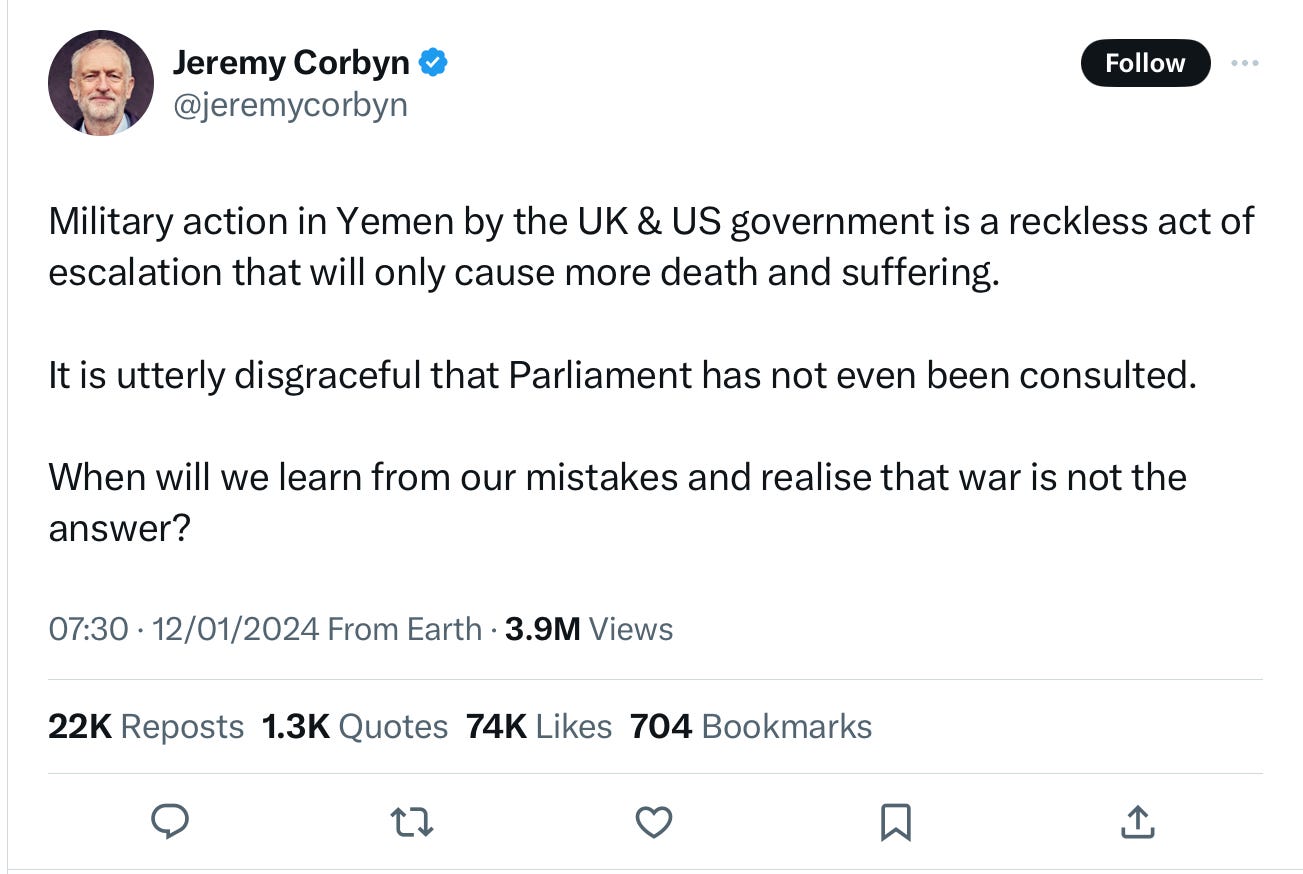

This hasn’t prevented several Parliamentarians from feeling irked that Rishi Sunak proceeded without informing them or asking for their consent. The decision was taken earlier on Thursday evening, with the Cabinet and Labour Leader Keir Starmer briefed ahead of time. The usual suspects were out in force. Jeremy Corbyn and members of the Socialist Campaign Group of backbench Labour MPs applied their sixth-form debate logic to the situation, decrying Britain’s response as an “escalation” and condemning the “disgraceful” lack of parliamentary consultation.

The far-left always takes this view, but the leaders of the Liberal Democrats, the SNP, and Plaid Cymru have all spoken out against the lack of information granted to Parliament too. This has sparked debate about whether the Prime Minister needed to consult Parliament and, if not, whether he should have done so anyway. This question, along with the complaints from backbenchers and opposition leaders, ignores the reality of defense policy. How can timely and dynamic action be taken against those who want to harm us if Parliament has to debate it every time? And what about the element of surprise?

It is completely acceptable, and indeed desirable, for the Prime Minister to act with our allies to defend our interests without asking Parliament first. Furthermore, involving Parliament in the process has previously resulted in catastrophic outcomes for British defense and the world. After decades of debate over this question, it’s time to settle it in favor of executive action.

So Can The Prime Minister Decide Alone?

Firstly, let’s clarify whether the Prime Minister has the power to act unilaterally in military matters. The Institute for Government provides an excellent explainer:

“Technically, yes. As we have clarified previously, 'The power to commit troops in armed conflict is one of the remaining Royal Prerogatives – powers derived from the Crown rather than conferred on them by Parliament.' This means the PM has a constitutional right to authorise military action.”

However, this has been complicated by Prime Ministers choosing to seek Parliamentary approval before taking military action and when the Coalition government made the following commitment:

“...to observe the convention that the Commons should have an opportunity to debate military action, except in an emergency, and this principle was subsequently included in the Cabinet Manual.”

In the last couple of decades, it has become more common to consult Parliament before engaging the military. This mixed approach has further confused things. Proposed action against the Libyan Government in 2011, the Assad regime in Syria in 2013, and strikes against ISIS in 2015 were all put before Parliament. More recently, in 2018, the May Government participated in strikes in Syria without seeking Parliament's view first. The level of complaint in the latter instance was similar to what we have witnessed since the strikes against the Houthis last Thursday.

Because the British constitution relies so heavily on precedent, the answer to whether the Prime Minister can act alone is both yes and no. Or, looking at it another way, the question remains unanswered and now represents the perfect opportunity to clarify things…

The Case Against Parliamentary Involvement

Effective military operations hinge on swift responses, adaptability, and the element of surprise. The involvement of Parliament hinders these components. It is difficult for Parliament to consider such action on a quick enough timescale, given MPs are often in different parts of the country and a military response can be needed with little notice.

Effective decision-making in this instance also requires access to all the facts, and involving Parliament hinders this requirement too. The Prime Minister has access to privileged information and high-quality briefings it would not be appropriate to share with every MP. Let’s not forget that there are those in Parliament who appear to side with the theocratic dictatorship in Tehran over the West.

“Let’s not forget that there are those in Parliament who appear to side with the theocratic dictatorship in Tehran over the West.”

By extension, if something is shared with parliament, it is also shared with the rest of the country. In the interests of national security, Parliament cannot be informed of everything, and given the high-stakes nature of armed conflict, surely we want someone with access to all the relevant information – i.e., the Prime Minister – to make these decisions?

Giving Parliament some sort of veto also exposes defense policy to party politics. In 2013, David Cameron, then Prime Minister, favored taking action in Syria, against a regime that was butchering its own people. Cameron, in keeping with the Coalition’s promise, chose to put the decision before Parliament. The then Labour leader Ed Miliband led a British body politic burned by the fallout from the Iraq War in opposing military action in Syria.

The result has been the perpetuation of the Assad regime, Russian atrocities filling the power vacuum, and a refugee crisis that strained the entire European continent. If David Cameron had acted in what he believed to be the best interests of the country, the outcome might have been different. The Prime Minister is the person best placed to make well-informed decisions on military action quickly, without revealing plans to our enemies. We are safer with executive action.

But Democracy? Iraq?

Of course, some may point to the Iraq War, which was driven forward with vigor by the Prime Minister of the day, as an argument against concentrating power in the hands of the PM. Was that war – or at least the public rationale for that war – not based on faulty intelligence? Sure, but that didn’t stop Parliament from backing it in multiple rounds of votes. The involvement of Parliament did nothing to temper the government's desire to invade Iraq.

While that debacle shows that Prime Ministers are perfectly capable of making bad decisions, acting in bad faith, or upon poor intelligence, this doesn’t change the fundamental trade-offs involved in taking effective military action or the fact that the Prime Minister's office is best placed to make these decisions - even though not every PM will make the right ones.

But what about democracy?! Surely involving Parliament is the democratic thing to do? Well, in most instances of policy, yes, and I’m certainly not in favor of some sort of executive dictatorship, far from it, I love democracy! Ultimately, if Parliament does not trust the Prime Minister and his government to make the right decisions on these matters at short notice, then it should remove that government via a vote of no confidence. Any other course of action is - or should be - a tacit approval of the Prime Minister's agency to act in defending the country.

“The involvement of Parliament did nothing to temper the government's desire to invade Iraq.”

While consulting a well-informed Parliament on every military strike would be ideal if it could also result in well-executed action, in reality, it can’t. This type of decision is different from most others involved in government. It’s also how many other democracies are run. So no, this isn’t executive overreach, nor is it the actions of a wannabe dictator. It's the leader of a government our democratic body has confidence in1, using the powers vested in him to defend our interests.

The current outcry against Sunak’s lone decision does at least help in one regard. It draws attention to the urgent need to codify this issue either way. The coalition’s addition to the Cabinet Manual is, as the Institute for Government sets out, far from clear. The Prime Minister and Parliament both need to know where they stand. Whatever side of this argument you find yourself on, we need to make a decision. In my view there is no better choice than vesting this power explicitly in the hands of the Prime Minister. It’s time we clarified once and for all that this is the best way to keep Britain safe.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece then please consider subscribing, it’s free and you have nothing to lose except a tiny portion of your life. If you’re already a subscriber then thank you! Please share this post with anyone who might be interested.

Whether it should have confidence in Sunak and his Government is another question entirely.