Trump's Intel Deal Is MAGA Socialism

Industrial policy in disguise is still industrial policy

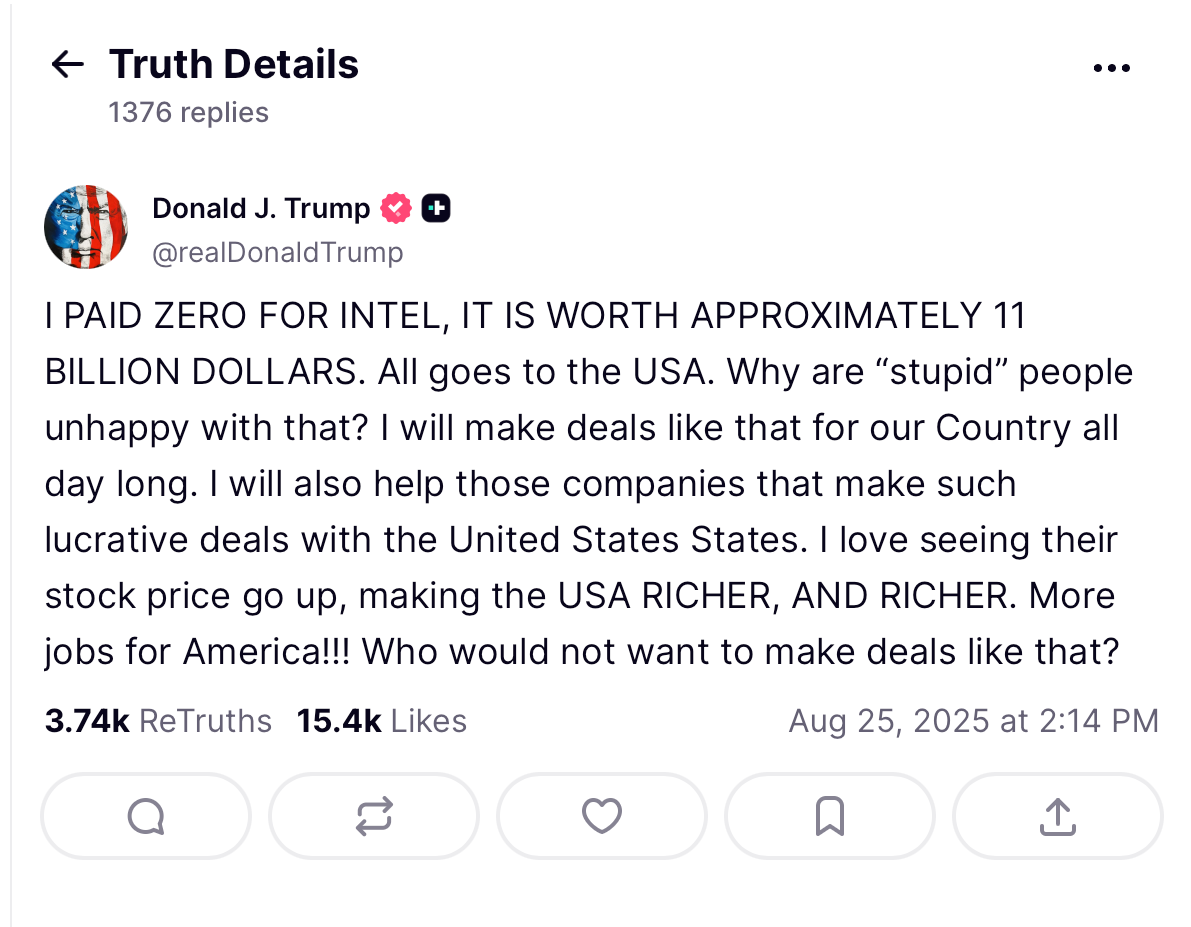

The US Government has become Intel's largest shareholder, converting Biden-era CHIPS Act support into a 10% non-voting equity stake in the struggling semiconductor giant. Trump touted the deal as "lucrative" on Truth Social, emphasising there's no upfront cost. Alas, the costs down the line could be large.

The deal scraps the clawbacks and profit-sharing mechanisms built into the original CHIPS framework, removing taxpayer protections while loading taxpayers with risk. After all, Intel is flailing precisely because consumers and businesses don't want its products.

National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett told CNBC this could be just the beginning:

"The president has made it clear, all the way back to the campaign, that he thinks that, in the end, it would be great if the U.S. could start to build up a sovereign wealth fund."

Don't hold your breath for that sovereign wealth fund to materialise. What we're really seeing is something more basic: the federal government is taking direct ownership stakes in private companies. Industrial policy in disguise is still industrial policy and it’s indicative of the leftism the Republicans bang on about hating. It is, if you will, MAGA Socialism.

Why Industrial Policy Doesn’t Work

The thing about industrial policy is that it asks government officials to make predictions about technology and markets that they just can’t do on their own. In a market economy, information about technologies, costs, and demand are dispersed and dynamic.

Policymakers don't have access to the dispersed, real-time signals about technologies, costs, and consumer demand that prices aggregate automatically. No government bureau knows which experimental chip designs will work, which manufacturing processes will prove cost-effective, or which companies have the management talent to execute complex turnarounds.

Private markets aren't perfect, but they're really good at this stuff. Venture capitalists, who do this for a living and risk their own money, fail to pick winners roughly 75% of the time. Government officials, spending other people's money with much weaker feedback mechanisms, aren't going to beat those odds.

But the bigger problem is incentives. When company profits start coming from government subsidies rather than selling better products, rational managers shift their focus accordingly. Why spend money on risky R&D when you can hire lobbyists instead? Incumbents get propped up while potential competitors with better ideas get shut out.

We have plenty of examples. Japan's industrial policy in the 1980s created some impressive-looking conglomerates that turned into zombies by the 2000s. France's national champions strategy produced companies that dominated domestically but couldn't compete globally. Even “successful” cases like South Korea's chaebols came with enormous costs – market concentration, corruption, and financial instability that culminated in the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The Intel case fits this pattern perfectly. The company's problems aren't about capital – Intel has raised billions from private investors and received substantial government support already. Its problems are execution and strategy. Intel has consistently missed product deadlines, failed to transition to mobile computing, and lost manufacturing leadership to TSMC and Samsung.

These are exactly the kind of problems that government ownership makes worse, not better. When the state becomes a major shareholder, political considerations start influencing business decisions. Procurement contracts, regulatory approvals, and tax policy all become tools for supporting the government's investment rather than neutral arbiters of competition.

Diversification Beats National Champions

The national security argument for supporting Intel isn't completely wrong. Concentrating advanced chip manufacturing in Taiwan does create vulnerabilities, especially given China's growing assertiveness. But there are better ways to address this than propping up a single struggling American firm.

The smarter approach is what's already happening: diversification through alliance networks. TSMC is building fabs in Arizona and Germany. Samsung is expanding in Texas. European and Japanese companies are making major investments in next-generation chip technology. This creates redundancy without putting all our eggs in one basket – especially a basket with Intel's track record of execution problems.

Think about the incentives here. Under the current approach, Intel gets guaranteed support regardless of performance. Under a diversified alliance strategy, different firms and countries compete for contracts and investment, creating continuous pressure for innovation and efficiency.

The structure of this deal makes it even worse. The government gets an additional 5% stake if Intel spins off its foundry business – which many analysts think is exactly what the company needs to do to become competitive again. So the deal actually discourages the restructuring that might help Intel succeed.

Meanwhile, Trump has made it clear that corporate support depends on willingness to cut similar deals with his administration. This creates a dynamic where business success increasingly depends on political favour rather than market performance, the kind of crony capitalism that leads to economic stagnation and widespread corruption.

The original CHIPS Act had better design. It used clawbacks and profit-sharing to give taxpayers upside exposure without the conflicts that come with direct ownership. Congress specifically chose these mechanisms to avoid the problems now being created.

I get that industrial policy has a seductive logic. When you see a foreign competitor like China making big state investments, it's natural to want to respond in kind. But this is always a big mistake. China's state-directed model creates massive inefficiencies, zombie companies, and debt bubbles that get papered over by authoritarian control and accounting opacity. Countries that try to copy this approach generally end up with all the costs – corruption, market distortion, resource misallocation – while lacking the political tools to hide the failures.

The better response is to double down on what competitive economies do well: open markets, strong institutions, and policies that reward innovation rather than political connections. That's a more boring story than "America fights back with its own industrial champions," but it's also more likely to work.

Thank you for reading Build Vector, if you’ve enjoyed this piece then please consider subscribing, it’s free and you have nothing to lose except a tiny portion of your life. You can find me on X @Jack_Nostalgic