The West’s Age of Adjustment

The longer we wait, the harder ageing will hit

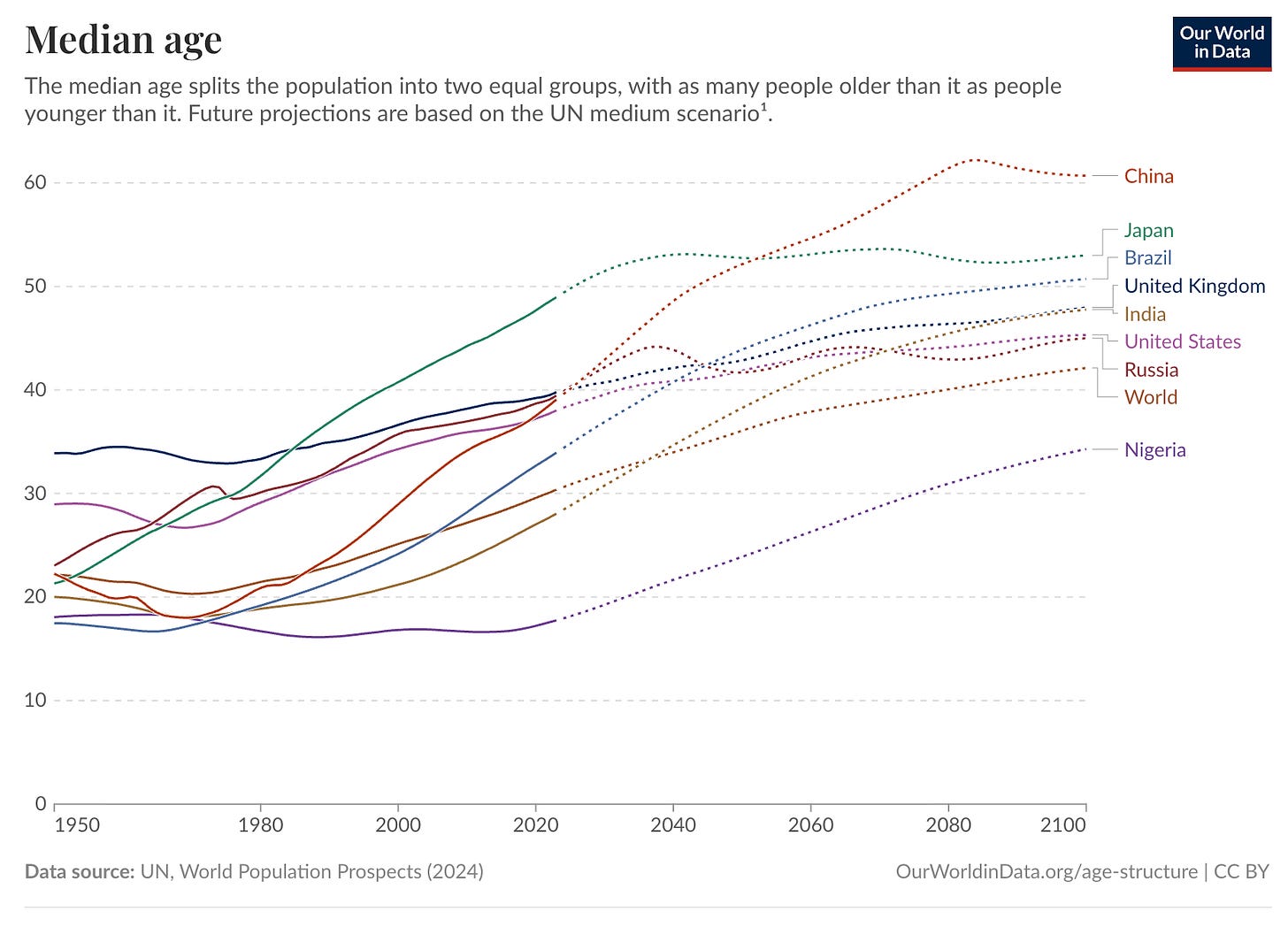

The West is growing old. No longer a distant worry, the crisis of our ageing society is here and it is accelerating. The median age of a Western European has jumped from 36 in 1990 to 44 today. In the United States, people aged 60 and over make up nearly a quarter of the population; that share will approach a third by 2050. In Britain, the fertility rate has fallen to 1.44 children per woman – the lowest since 2001.

These figures are far from abstract. Without change, a shrinking workforce slows growth and tightens the public finances. Fewer working-age taxpayers mean more trade-offs in state spending.

As each generation becomes smaller than the last, the risk is that the optimism and dynamism that powered the post-war West may erode. Whether our political systems can handle predictable demographic change without sliding into decline will be the ultimate test of state capacity.

Chequebook Pro-Natalism Does Not Work

To avoid demographic decline, countries need to reach a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 2.1 children per woman. The argument from the pro-natal movement is simply to throw money at the problem. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests such policies do not work, or cost so much as to be unfeasible.

South Korea – with its measly TFR of 0.75 – has spent the better part of $270 billion trying to reverse its baby bust, but no amount of money has so far reversed the lowest fertility rate in the developed world. Neighbouring Japan has spent as much as 0.6% of GDP a year on family spending, but births still fell below 700,000 in 2024 for the first time.

Even where chequebook pro-natalism does have an effect, the impact tends to plateau below the replacement rate whilst costing a bomb. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s national-conservative government has devoted a large portion of the economy to family policy – some 3.5% of GDP. Its fertility rate rose from 1.25 in 2010 to 1.6 in 2021 but has since stalled.

Short-term successes, meanwhile, tend to fade. Spain’s €2,500 baby bonus in 2007 produced a brief spike in births before the decline resumed. Financial incentives mostly shift the timing of births rather than the total number over a lifetime.

Besides, ageing societies already face rising pension and healthcare costs. I am prepared to believe that there is a price point at which people would be meaningfully encouraged to have more children, but it is probably too high to be realistic. And I am not sure we want people to have children solely for financial gain. Committing to large, permanent outlays for modest demographic returns is a fiscal gamble not worth taking. That is perhaps why most Western governments have looked elsewhere for relief.

Import The Young

Instead of reckoning with the problems of demography, too many Western nations have put their fingers in their ears and hoped that migration will save them. The argument is a simple one: we can import young people from abroad to prop up our ailing dependency ratios.

The problem with this approach is manifold. For a start, large inflows of people prepared to work for low pay are a drag on productivity. In sectors with ready access to low-wage migrant labour – hospitality, agriculture, low-end manufacturing – companies are less likely to invest in automation or reorganise work for higher efficiency.

In some cases, migration can make the problem worse; generous welfare systems and lax entry requirements can mean an influx of foreign labour working for low pay whilst drawing money out of the system. Analysis by the Centre for Policy Studies showed that 72% of migrants to the UK on skilled worker visas earned less than the national average salary; 54% earned less than half the national average salary.

All of this is before we even begin to reckon with the societal issues of having to integrate many new people every year. It is perfectly possible – and indeed desirable – to have some net immigration without culture clashes, but it requires a dedication and focus that is unrealistic to extend to 500,000+ people every year.

And besides, there is not a limitless supply of global labour. Immigrants age too, and the evidence suggests that fertility among migrant groups tends to converge with host-country norms within one or two generations. Some high-skilled migration can bring talent and new ideas and can help alleviate the worst effects of our demographic crisis. But it is not a silver bullet, and it must be managed carefully.

Adapting Hard and Making It Less Costly To Have Children

We cannot wish ageing away. Instead, we must look to make tough fiscal choices in order to adapt, whilst also tackling the supply-side reasons why people who do want children are not having them.

One lever is retirement. Raising pension ages is unpopular but effective. UK data show that increasing the state pension age by one year cuts the probability of retiring that year by about six to eight percentage points. Paired with flexible work options, retraining, and better disability support, these changes can keep more people in the labour force without undue hardship.

Another is unlocking underused labour. Affordable childcare has a proven effect on maternal employment. In Germany, expanding under-three childcare raised participation by around 0.2 percentage points for each percentage-point increase in available places. Better work-life balance policies matter too.

Technology, too, will be critical. Ageing is already correlated with faster robot adoption, and the care sector in particular will need investment. Japan’s trials of robotics in eldercare have cut the physical strain on workers and improved service consistency. This is the sort of adaptation that compounds — each year of adoption and refinement makes the technology more affordable and effective. Technological and workplace reform will work better if paired with changes that make family life viable in the first place.

But for many young potential families, the issue is not desire but housing and insecure living. High house prices are a scourge across the western world; in the UK, homeownership has almost halved among 25–34-year-olds since the 1990s. Planning reform and pro-density urban policy can help here, shaping the environment in which family decisions are made.

Time costs matter too. Parents benefit from predictable work hours, guaranteed childcare places, and parental leave that replaces a high share of income but is clearly time-limited to encourage a return to work. These policies help parents balance careers and family without permanently pushing one partner — usually the mother — out of the labour force.

Another factor is partnership formation. Research in the US shows that wage stagnation among men in their 20s and 30s correlates with lower marriage rates. Making urban living affordable for young adults is not just an economic issue; it also shapes the likelihood of forming families.

The aim here is not to push women out of work or back into the home. It is to create a framework where work and family can realistically coexist, so that having children does not require career sacrifice on one side and financial strain on the other. These family-friendly reforms must sit alongside the productivity and participation measures outlined above — rather than be considered an optional extra.

Ageing is the most predictable macroeconomic challenge the West will face this century. If our politics cannot muster the will to prepare for it, then we will be doomed to experience slower growth, more debt, and diminished dynamism. The bill will come due whether we act or not. It is much better to pay for it in foresight than in decline.

Thank you for reading Build Vector, if you’ve enjoyed this piece then please consider subscribing, it’s free and you have nothing to lose except a tiny portion of your life. You can find me on X @Jack_Nostalgic