Labour’s Re-Regulation Gamble

The Employment Rights Bill is the Wrong Cure For An Ailing Economy

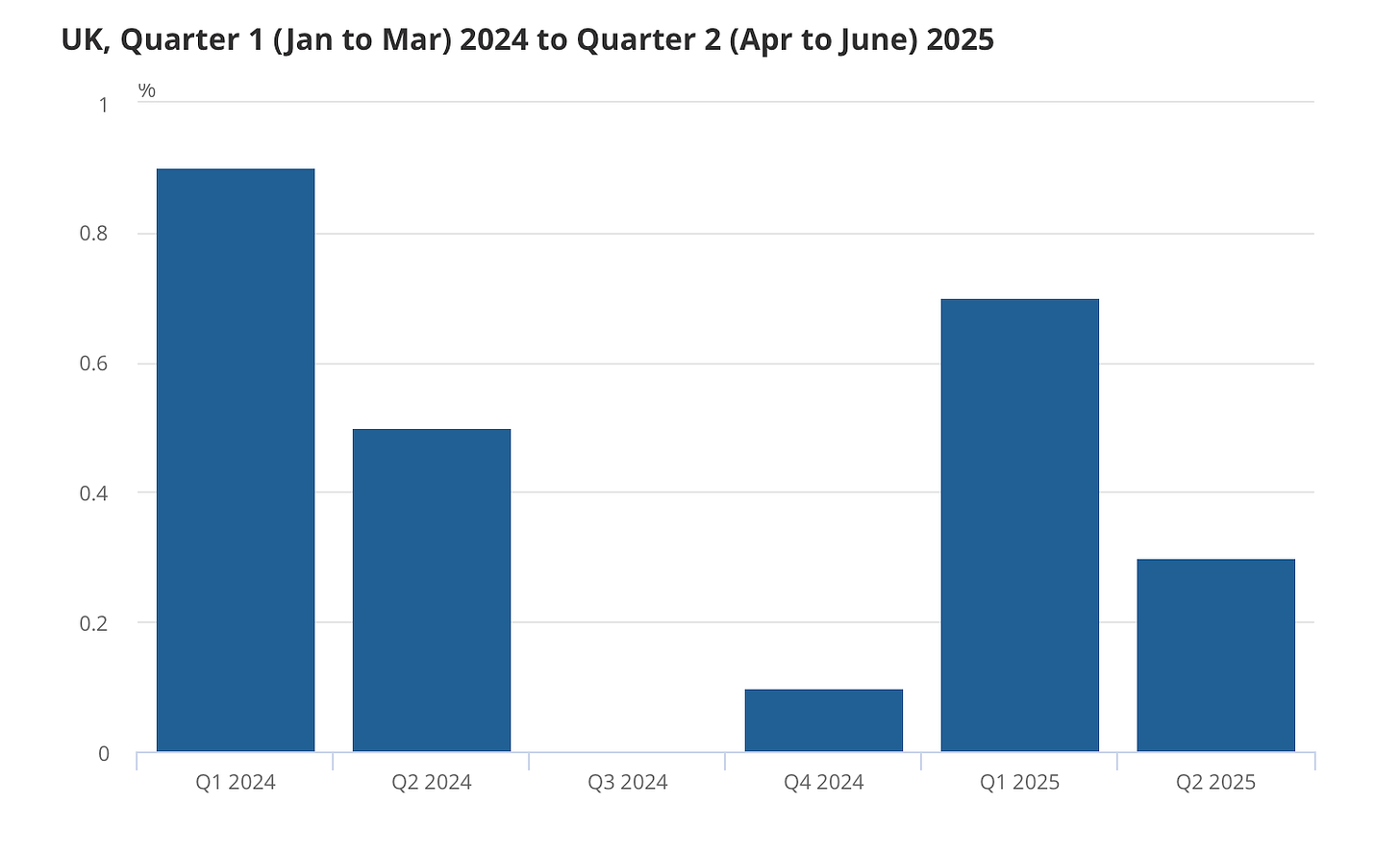

Over the past few weeks I’ve been watching the economic numbers trickle out, and the picture that emerges is of a country that is technically growing but in a way that doesn’t inspire much confidence. GDP was up 0.3 per cent in the second quarter, which is fine as far as it goes, but the composition of that growth matters more than the headline.

When you dig into the ONS tables you find that most of the expansion came from government consumption and a rebound in construction, padded by a few quirks in inventories. Business investment, the thing you really want to see rising if you care about long-term prosperity, actually fell by four per cent, and production shrank too. So yes, we avoided a flatline, but only because the state carried us over the line.

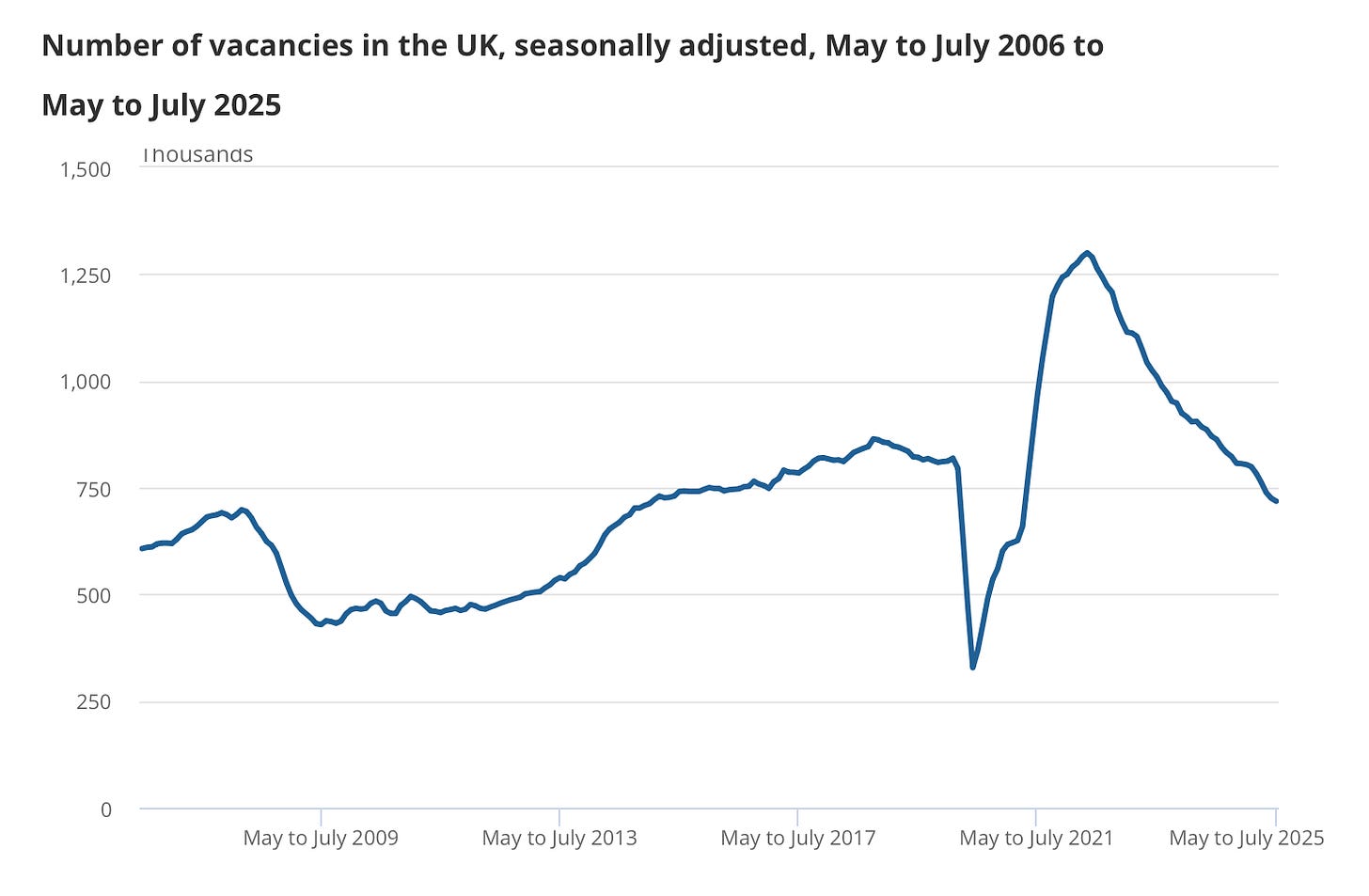

The labour market tells a similarly grim story. For years Britain’s high employment rate was the best evidence that, however sluggish productivity might be, we were at least creating jobs. But now the gloss is wearing off. Payrolled employees have fallen six months in a row, vacancies have been sliding for more than three years, and unemployment has crept up to 4.7 per cent — still low historically but the highest in four years.

Recruiters report that starting salaries are barely rising, which suggests employers no longer feel the same pressure to compete for talent. Meanwhile overall wage growth remains close to five per cent, too high for the Bank of England’s comfort. Put those two things together and you get a messy picture: a market that is loosening even as pay settlements stay strong, the kind of situation that makes central bankers nervous.

If the jobs numbers are worrying, the state of the public finances is downright alarming. Borrowing in June hit £20.7 billion, the second-highest June on record, thanks largely to eye-watering debt interest payments on index-linked gilts. Debt has climbed to more than 96 per cent of GDP. That alone would be a warning sign, but what makes it worse is that the Treasury is already overshooting the OBR’s borrowing forecasts.

Against this backdrop, Labour is preparing to unleash the most sweeping programme of workers’ rights reforms in decades. The bill currently moving through Parliament will repeal the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act, unwind much of the Trade Union Act 2016, and make industrial action easier to call and harder to punish.

From 2026, statutory sick pay will be expanded, the lower earnings limit scrapped, waiting days abolished, and a new Fair Work Agency created to enforce it all. By October that year fire-and-rehire will be heavily restricted, probationary periods codified, and employers made liable for harassment prevention.

From 2027, zero-hours contracts will be replaced with guaranteed hours and compensation for cancelled shifts, while “day one” unfair dismissal protection will become the norm.

The government has also told the Low Pay Commission to map out a path towards a single adult minimum wage, sweeping away existing age bands. This is a fundamental re-regulation of the labour market, a bad idea being pushed through at an even worse time. And it’s not as if these reforms land in isolation. Labour has already raised the cost of employment through April’s increase in employer National Insurance contributions and the sharp hike in the National Minimum Wage.

I understand why these proposals appeal politically. Talk of dignity and security resonates in a country where many people feel battered by the cost-of-living crisis and alienated by the rise of insecure work. Plenty of voters believe their jobs deliver less stability and fewer benefits than those of their parents’ generation, and in some sectors that is true. But Labour’s response is to treat the problem as one of insufficient legal rights, when in reality the central problem is that the economy isn’t growing fast enough. Security cannot be legislated into existence if firms aren’t confident enough to invest, expand, and hire.

The timing, in particular, seems reckless. Britain is not on the verge of an investment boom; it is struggling to get capital spending up at all. Employers are already retrenching, and smaller firms in particular will struggle with the new obligations.

Covering sick pay from day one, guaranteeing hours, and navigating stricter dismissal rules might be fine for a large multinational with a legal department, but for a small manufacturer or a family-run firm it represents a serious new cost. The predictable response will be fewer new hires, less willingness to experiment with flexible work, and a generally more defensive posture from businesses that already feel squeezed.

There is also the competitiveness angle, which cannot be ignored. The UK has spent years trying to lure investment in high-growth sectors like AI, biotech, and advanced manufacturing, but those sectors are mobile and they value flexibility.

If Britain moves in the opposite direction, loading the labour market with rigidities while rivals advertise dynamism, it will inevitably lose out. Investors comparing locations will not be fooled by the rhetoric about dignity and fairness; they will look at the rules on hiring and firing and draw the obvious conclusion.

Then there is inflation. If Labour’s reforms strengthen unions’ bargaining power and expand statutory protections, the risk is that elevated settlements become entrenched. Without productivity gains to match, firms will either raise prices or cut jobs. The Bank of England will keep interest rates higher for longer, and households will face the consequences. Far from making workers better off, this could easily leave them worse off in real terms.

The defence Labour offers – that secure workers are more productive workers – is not wrong in every case. High-skill firms do benefit when they can retain trained staff. But that logic does not scale to an entire economy. The historical lesson from the 1970s is that trying to force security in the absence of productivity growth is a recipe for stagflation. Britain paid dearly for that mistake before, and it seems remarkable that we are preparing to repeat it in a subtler but still damaging way.

At the same time, peers abroad are trying to tilt the playing field in the other direction – pushing through reforms that make it faster to build factories, lay down transmission lines, and get clean-tech projects permitted. The EU’s new industrial laws hard-cap approval times, the U.S. has rewritten its environmental review rules to impose deadlines, and Germany and the Netherlands have streamlined their planning systems to cut down on duplication.

The global race is about who can offer the smoothest path for capital to flow into the industries that will drive the next generation of prosperity. Britain, by contrast, is choosing to add new rigidities in the labour market, signalling caution to investors at precisely the wrong moment. The juxtaposition does not flatter us.

There is a better path, and it starts with growth. If you want dignity at work, the best way to provide it is to ensure that the economy is creating abundant opportunities, alongside plentiful jobs, and rising productivity. For a start that means fixing housing and planning and delivering abundant energy. In that kind of environment, workers have genuine bargaining power that flows from demand for their labour, not from a tribunal form.

Right now, though, Britain is heading in the wrong direction. Growth is fragile, the labour market is softening, the public finances are strained, and instead of addressing those issues the government is re-running old arguments about security versus flexibility. The warning lights are already flashing; if Labour ploughs ahead, they risk turning a weak recovery into a policy-driven downturn.

Thank you for reading Build Vector, if you’ve enjoyed this piece then please consider subscribing, it’s free and you have nothing to lose except a tiny portion of your life. You can find me on X @Jack_Nostalgic